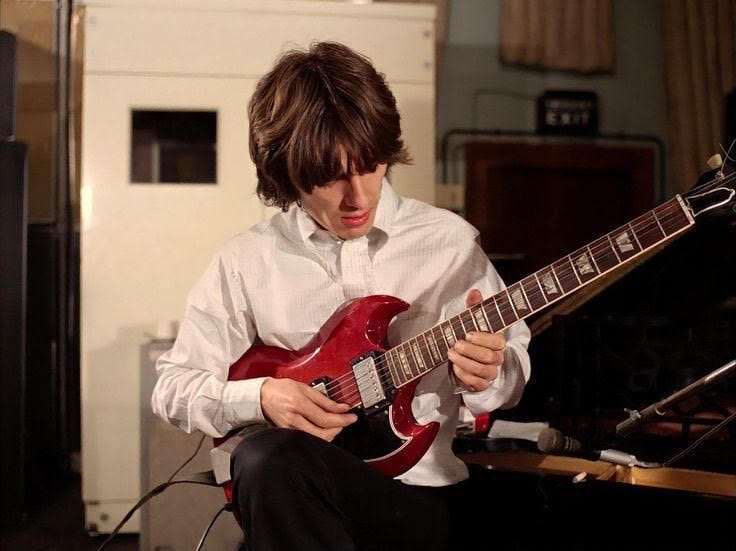

the former Beatle’s take on sound, stillness, and the art of listening.

As much as I respect and love the other band members’ music, there is something so unique and comforting about George Harrison’s. The reason why that is, is because his albums form a place within the songs themselves, and they remind me of a place of my own experience at the same time. For example, I cannot listen to All Things Must Pass (1970) without thinking of the valley road on my way to my aunt’s house, and every time I take that road, the feelings I associate to the album come up.

George Harrison’s songs rarely chase you down. On the contrary, it feels as though they wait. They seem to assume that if you’re here, you’re willing to stay awhile – to let melodies unfold, to sit with repetition, and to notice how feeling accumulates quietly rather than all at once.

You don’t really pass through his work so much as enter it, settle into it, return to it when you need a certain kind of stillness. At least, that’s what happened to me.

Albums as Inward Environments

Harrison’s albums feeling like places comes from how he approaches them as cohesive environments instead of potential standouts or hits. It is pure music defined by mood, pacing, and emotional continuity. And individual tracks do matter, but they gain their full weight when put in relation to one another. It’s not about telling a story or anything like that, it’s very different. Songs echo and refract the same concerns from different angles, until a particular emotional climate takes shape.

The album I mentioned above titled All Things Must Pass is the clearest expression of this instinct. Its sheer scale – layered guitars, musical gestures, expansive arrangements – represents slow buildup. There’s also a lot of repetition in his work, but I’ve never felt that it was for endurance as much as it was for immersion. The album unfolds at this pace deliberately. The instrumentality and lyrics invite you to move through it, whatever emotion you’d like to associate it to, slowly enough that the details begin to register. To me, this accurately mirrors the road to “acceptance,” for example, and I get reminded of these songs very often when I go through this difficult emotion/destination in all the different cases it can show up as.

Brainwashed (2002) is another album I’ve sat with, which offers a striking contrast – not by abandoning this world-building impulse but by distilling it. Its songs are shorter, the arrangements lighter, yet the sense of coherence is just as strong. It’s a different take on acceptance, with humor and reflection, but less of a statement and more of a continuous state of mind. Same emotion, different environment. Hence why the claim that Harrison is an artist more concerned with creating inhabitable spaces than chasing immediacy holds. It’s also why they’re meant to be sat with as aforementioned, to follow the pacing as it’s set, and to become places you can return to, familiar and quietly sustaining.

Spirituality as Atmosphere, Not Instruction

Spirituality is often treated as the subject of George Harrison’s music, but it’s more accurate to describe it as the atmosphere in which that music exists. Make no mistake, these aren’t instructions or declarations of belief. It’s clear he doesn’t even need to do that. It’s simply an emotional climate shaped by searching, patience, and repetition – much like the act of spirituality itself, but one that allows uncertainty to remain unresolved. Faith, in his world, isn’t a conclusion. It’s a continuous process, and not an easy one.

If you listen to “My Sweet Lord,” a song frequently flattened into the idea of a mantra, you’ll come to realize it is the opposite of assertion. The song builds slowly, voices gathering one by one, intention forming through kind repetition. It’s a very communal song, in the sense that it simply invites participation, allowing the listener to arrive at their own pace, and interpret the lyrics and feelings however they like. Its layered nature is what makes it one of my favorites of his.

Elsewhere, Harrison’s approach is even more understated. “The Lord Loves the One (That Loves the Lord)” unfolds with a conversational ease, offering reassurance without sermonizing. The song is a reminder that a truth needs warmth and care in lieu of instruction. Similarly, “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)”’s lyrics reach upward, but the melody stays grounded, carrying humility and doubt alongside hope, the pillars of the human condition.

Spirituality lives in the way Harrison repeats phrases until they soften, in the way melodies linger without resolving too quickly, in the space he leaves around his words. Meaning emerges gradually, through patience and attention. The result is music that makes room for belief to feel fragile, incomplete, and – because of that – deeply human.

Sound as Spiritual Language

Spirituality in George Harrison’s music goes beyond words and themes; it is carried, just as powerfully, by sound itself. Through texture, pacing, and sometimes restraint or silence, the sound is the philosophy.

Harrison’s slide guitar is the central component to this language. Across albums like All Things Must Pass and Cloud Nine, it functions as conversational. Notes linger and bend, emotion carried through sustain, and feelings surface gradually. On paper, this might feel slow, but in practice? Expressive and charged with attention and care with all the comfort embedded.

To accompany the guitar, Harrison uses several techniques that render his music so meditative: Indian instrumentation that sort of reshapes time itself and Gospel choirs that support shared searching and serve as a communal breath are two of many others. All of these choices we discuss reveal how deeply Harrison trusted sound to carry meaning. And that spirituality so often associated with his music mainly comes from an important ingredient he successfully managed to work with: patience. Ultimately, it is yet another reason for the claim that listeners end up experiencing a state of mind instead of feeling like they are receiving a lesson.

Doubt, Frustration, and the Human Presence

In the spirit of introspection, comfort and patience, the worlds Harrison builds are never sealed off from strain. They are spaces where doubt, fatigue, and frustration move freely, grounding his music in lived experience and straying it away from abstraction, the former being something we all sometimes need a dose of. Friction between intention and reality, between patience and impatience, between belief and the persistent pull of ego are all normal and acknowledged.

One song I think of here is “Beware of Darkness”, which stands at this intersection of warning and vulnerability. It presents an understanding that forces being named are difficult to escape, even with awareness. The unease in the music, the way it never fully settles, mirrors that internal tension. Or even in “Who Can See It,” a song that carries a weary clarity, accepting limits without collapsing into bitterness. It talks about someone who has stopped struggling for resolution and learned to sit with what can’t be changed – again, a difficult thing to do, but proof that it is real, and that “someone” is not alone in fighting it. I also think of “The Day the World Gets ‘Round,” another song with a circular structure and which returns again and again to the same questions, highlighting the co-existence and tension between hope and weariness.

There are many more I could name, but these are the moments that keep George Harrison’s music human and inhabitable as well. Doubt is allowed to remain, unresolved and honest. By making room for frustration and uncertainty, Harrison ensures his musical worlds feel shaped by real and lived-in experiences rather than idealized distant conviction.

Of course, this doesn’t mean there is no humor or sincerity. On the contrary, his work is that precise assertion of independence – the right to be odd, private, and sincere without explanation, creating those inner worlds ourselves within his, that don’t need to justify themselves. These moments complete the atmosphere Harrison builds. They remind the listener that reflection doesn’t require solemnity, and that searching can coexist with levity. His musical worlds are shaped in conversation with reality itself, responding to confusion, absurdity, and contradiction with a steady, knowing calm.

When You Grow Into the Music

I can only compare my listening experience of his work to a year prior, because I’ve only known him for that long. Even so, the change and growing effect are already noticeable. Themes of impermanence, aging, and acceptance move closer to the surface – lighter, more understanding, rather than surrendering. It doesn’t feel so scary anymore.

I remember the first time I listened to Cloud Nine. It captured this shift with an ease that felt earned. The George Harrison I encountered here was slightly different from the one I started with: bright, relaxed, and confident without urgency. The album reflected an artist at peace with his voice and its limits. The world it built was open and welcoming, shaped by experience rather than ambition – and I realized I needed to get to know it, too.

Some listeners note the tones of mortality in his later work, as Harrison approached the end of his life. Yet even when those themes appear, they remain patient and accepting rather than heavy. I’ve always felt that he reads pages from his journal in his songs, even in the music itself, tackling death or difficult truths without dramatization. A reminder that little is needed to express something lasting, and the restraint only makes it more profound.

It’s music that doesn’t change all at once, but changes with you, over time and with patience.

Listening to George Harrison now feels like an act of recalibration. In a culture shaped by speed and constant interruption, his music quietly insists on another way of being with sound – one that values patience, continuity, and return. These albums reveal themselves most fully when heard whole, when allowed to unfold without distraction, and when revisited over time.

I highly encourage you to take a dip in his solo work, I know it has helped me better cope with our world. Because also, his music doesn’t compete for attention. It waits – confident that, when you’re ready to listen, it will still be there.

Leave a comment